Mind matters: 8 ethical questions about experimenting with human brain tissue

Lab-created consciousness, especially resulting from testing human brain tissue, sounds like the plot for the newest binge-worthy TV show, but it’s a matter worth consideration from an ethical perspective, according to some experts.

A group of 17 researchers—led by Nita A. Farahany, the director of the Duke Initiative for Science & Society at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina—examined issues that may arise as scientists get closer to replicating human brain functions, publishing an April 25 paper in Nature.

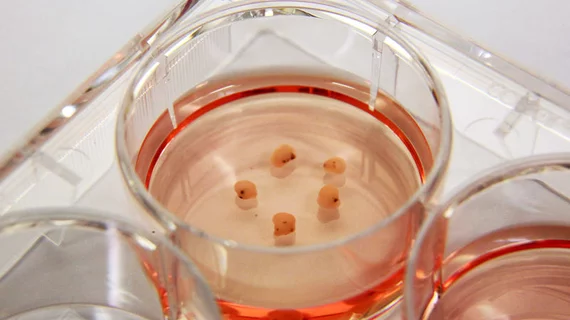

The authors cited development of so-called “brain organoids,” or miniature versions of brain tissue grown from stem cells, as evidence that experimental models are at the point where deeper ethical questions

“[T]he promise of brain surrogates is such that abandoning them seems itself unethical, given the vast amount of human suffering caused by neurological and psychiatric disorders, and given that most therapies for these diseases developed in animal models fail to work in people,” Farahany et al. wrote. “Yet the closer the proxy gets to a functioning human brain, the more ethically problematic it becomes.”

The team first outlined three classes of surrogates that could supply researchers with avenues to exploring brain activity without exposing people to risky and ethically questionable procedures.

Organoids: These aggregates of pluripotent stem cells are able to self-organize into 3D structures similar to those in areas of the brain.

“[T]he possibility of organoids becoming conscious to some degree, or of acquiring other higher-order properties, such as the ability to feel distress, seems highly remote,” the authors wrote. “But organoids are becoming increasingly complex. Indeed, one of us recorded neural activity from an organoid after shining light on a region where cells of the retina had formed together with cells of the brain. This illustrated that an external stimulus can result in an organoid response.”

Tissue removed from living individuals: Brain matter that has been removed during medical procedures may provide researchers with slices of tissue to be studied. Operations to the neocortex—to help treat epilepsy, for example—result in samples that may help researchers.

Chimeras: The third category focuses on transplanted human cells implanted into the brains of animals. Scientists have already implanted human glial cells into mice, as one example.

“Such chimaeras are generated to provide a more physiologically natural environment in which the human cells can mature,” Farahany et al. wrote.

The authors cited eight issues to consider as such work advances.

Metrics: Is it possible to assess the consciousness of a brain surrogate? Where is the line drawn?

Death: Similarly, if living brain tissue is used in the lab, how does this redefine death? Advancing treatment of neurological problems may challenge accepted norms for brain death.

Human-animal distinction: If human brain cells are implanted and grow in an animal host, how does this effect the dividing line between species? A pig with a human kidney is one case—a human-like brain structure in an animal is more challenging.

Consent: Must researchers reconsider how consent is granted for research into brain tissue?

”[R]esearchers using pluripotent stem cells or brain tissues generally disclose their plans to donors in broad terms,” the authors wrote. “Given how much people associate their experiences and sense of self with their brains, more transparency and assurances could be warranted. Donors might wish to deny the use of their stem cells for the creation of, say, human–animal chimaeras.”

Stewardship: Would chimeras or brain surrogates require guardians or individuals looking out for their best interests?

Ownership: Who owns ex vivo brain tissue?

“If significant developments in the field one day lead us to regard any of these brain surrogates as having greater moral status than we would currently give them, might greater privileges and protections be appropriate?” wrote Farahany and colleagues.

Post-research handling: What protocols need to be in place for disposing of brain tissue once it is no longer needed?

Data: Should there be procedures or requirements for data sharing, collaboration and legacy use of brain tissue?

These questions should not halt current research, the authors said. Rather, these ethical concerns should be considered before advancements in technology put scientists in difficult positions. The team noted efforts to tackle these thorny subjects, but the field needs to do more.

“Existing institutional ethics review boards or those for stem-cell research oversight might not yet be equipped to address issues specific to these experimental brain models because they are so new,” Farahany et al. wrote. “We recommend that such organizations ask experts in this area to join their boards or serve as consultants. New committees, dedicated to overseeing the use of human-brain surrogates, could also be assembled.”