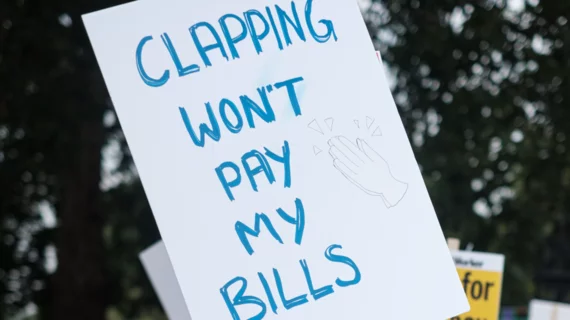

‘Undervalued’ UK physicians register discontent over fading ‘purchasing power’

Going by compensation rates and trajectories, these might be the worst of times to be a physician in the United Kingdom.

It would be hard to draw a different conclusion from an analysis conducted by British journalist Adele Waters for The BMJ on behalf of the Office of Health Economics (OHE), an independent health economics research organization based in London.

The BMJ published the article online March 20.

The analysis shows that salaries of physicians declined in real terms by 25%, on average, in the years between September 2008 and September 2023.

Given the steady rise in the cost of living, Waters shows, the protracted period of pay erosion adds up to a substantial reduction in “purchasing power.”

Most physicians in the country are employed by the National Health Service, but the big dip holds not only across public and private lines but also across distinctions of seniority and specialty.

Further, the 25% hit for doctors compares with 10% across all work sectors, Waters notes.

The author points out these numbers line up with figures in earlier research by the British Medical Association. That study, conducted in 2023, concluded doctors would require a 35% raise to correct the 25%-plus pay erosion with which they’ve lived since 2008. (It was during the global financial crisis of 2008 that U.K. physicians first had their pay frozen.)

Bearing the brunt

Noting that paycheck shrinkage is “disproportionately affecting lower grade doctors”—not least those still in the training or “junior” years of their practice—Waters quotes the co-chair of the BMA’s junior doctors committee, Vivek Trivedi:

“Both the private and public sectors experienced a fall in pay in real terms after the financial crash in 2008. But in the private sector, which makes up 80% of the U.K. workforce, we saw pay levels rebound relatively quickly, while the public sector bore the brunt of austerity. And within the public sector, doctors have taken a specifically harder hit—so the level of pay erosion has been even stronger.”

Another young physician Waters interviewed, Penelope Sucharitkul, says:

“I always thought doctors would be able to afford to have a wedding or to buy a house. And now I find I’m not really managing to save much at all. If I didn’t [live in a two-income home], I’d be struggling a lot more.”

Deepening despondency

Waters also spoke with several policy experts. One, Annie Williamson, NHS junior doctor and associate researcher at the Institute for Public Policy Research, says:

“The stark reality of falling real pay for junior doctors deepens despondency and our sense of being undervalued. Every colleague leaving for Australia cites the squeeze on pay, yet we need the NHS to deliver first rate care more than ever. The first step must be to recognize and retain the hardworking staff that form the backbone of this service.”

The full analysis is here.

Meanwhile The Guardian reports that close to 100% of junior doctors in England have backed a motion to continue striking over pay dissatisfaction, as they’ve been doing for more than a year.