Stanford study questions how medical AI devices are evaluated

Every day, more AI uses are coming to market, with medical devices a perfect target for innovating healthcare. And while more than 130 of such tools have been approved by the Federal Drug Administration, some experts are saying the review process needs to be reevaluated.

That’s according to a group of Stanford researchers who wanted to know how much regulators and doctors actually know about the accuracy of the AI devices they are touting and approving. The evidence may actually reveal some of the faults with AI technology, according to the study, which was published in Nature. The researchers analyzed every AI medical device approved by the FDA between 2015 and 2020 for their study.

They found that approval for AI devices was starkly different than the approval process for pharmaceuticals.

The biggest problem lies with historical data being used to train AI algorithms. In many cases, this means the data is outdated. Many algorithms are never actually tested in a clinical setting before being approved, and many devices were also only tested at one or two sites, limiting the inclusion of data from more racially and demographically diverse patients.

“Quite surprisingly, a lot of the AI algorithms weren’t evaluated very thoroughly,’’ said James Zou, the study’s co-author, who is an assistant professor of biomedical data science at Stanford University as well as a faculty member of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI).

This also meant that AI devices weren’t being assessed for live patients in real settings. Instead, the predictions and recommendations were based on retrospective data.

This realization may mean that AI medical devices may actually fail to capture how healthcare providers can actually use these tools in clinical settings. The same is true for different demographics.

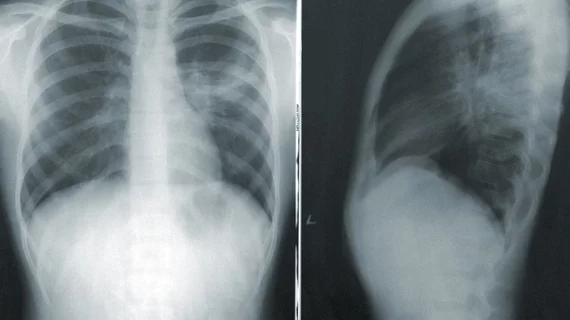

The researchers pointed to a deep learning model that analyzes chest X-rays for signs of collapsed lungs to prove their point. While the model worked accurately for one cohort of patient data, against two other patient data sites, the algorithms were 10% less accurate. Accuracy was also higher for white patients than for Black patients.

“It’s a well-known challenge for artificial intelligence that an algorithm may work well for one population group and not for another,” Zou said.

The findings may inform regulators about the challenges of AI medical devices and reveal a need for stricter approval requirements.

“We’re extremely excited about the overall promise of AI in medicine,” Zou said. “We don’t want things to be overregulated. At the same time, we want to make sure there is rigorous evaluation especially for high-risk medical applications. You want to make sure the drugs you are taking are thoroughly vetted. It’s the same thing here.”